The Two of Three Rule#

How do you decide when to join a company, when to stay and when to leave?

I’ve worked at my fair share of companies, both in and out of the computer technology space. I don’t think I’m leaving companies because I have a problem with consistency; in fact it’s quite the opposite.

I’m a trained statistician. I worked on a motorcycle manufacturing shop floor for 3 years of my early career, and compared to tech companies, that was hell. However, the lessons I learnt there have moulded me forever.

The most important lessons revolved around a statistical quality tool called control charts or Shewart charts, named after Walter A. Shewart, who pioneered them. Shewart’s name is spoken in the same tones as that of Deming, who is responsible for the 14 Principles of Management.

An Aside - Control Charts#

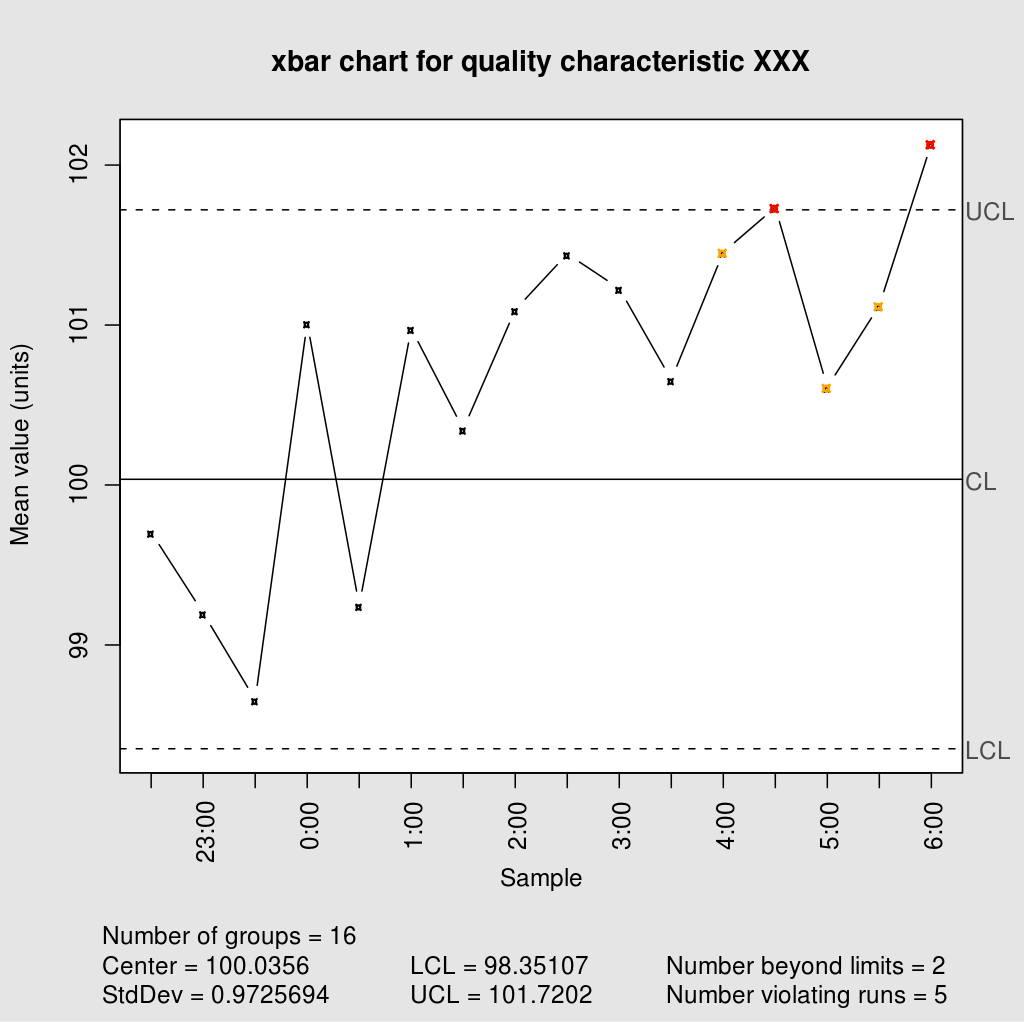

A control chart, in its multiple forms, monitors a process for changes in a specific parameter, designated as the control parameter. This parameter helps us measure a desired outcome of a process. If a factory wishes to produce a shaft of diameter 25mm with a tolerance of 1mm on either side, then they should strive to make shafts from 24-26mm in size. While that’s a worthwhile exercise, it’s better to further limit the manufacturing process so that while the process sticks to the design requirements, it is also consistent within itself. This doesn’t mean you’re striving for a better design tolerance, but it speaks about whether your process even allows for better tolerances. The control chart is a line plot that measures this parameter, or a statistic associated with it such as the average of a couple of readings taken at consistent timestamps. Control charts are divided into 2 areas, a portion of the chart is above a line called the control limit (CL), and the range of values is bounded on either side by an Upper Control Limit (UCL), and a Lower Control Limit (LCL), which tell us how much our process is capable of fluctuating.

A sample control chart, marking the limits and showing how a process is slowly deviation from its control limits.#

These limits aren’t decided by us. Indeed, they have nothing to do with the tolerances that the design engineer has set. Instead, they have everything to do with the statistical limits of your process. That means that the last 25 readings you take in your process decide the UCL, CL and LCL for the next couple of readings.

Tip

25 is an arbitrary number, mind you. It is the bare minimum that you need to start plotting charts. However, it is not even statistically viable to do this. Instead start with a 100 readings if you want to do some meaningful analytics of process control study.

If 7 consecutive readings on a control chart fall on one side of the limits, that’s your chart telling you that you have serious problems. Your process is slowly deviating to one side of your limits. It doesn’t need to be negative by the way. Perhaps you want your process to shift in one direction. This is an indication that whatever you’re doing to your process is shifting the metric to one side.

These shifts are predicatable, and they also indicate a shift in your process that could arise from inherent causes. However, there are sudden shifts that could happen because of uncontrollable causes. These problems will not cause long-lasting errors in your readings, and they’re usually the sort that need a lot of brain-wracking to solve immediately. If they’re not addressed immediately, this will indicate that something is really wrong with your process management, and not really reflect whether your process is doing well or now.

While a control chart is something you can definitely use in technology companies – in fact, control charts are strongly associated with LEAN manufacturing, but I’m not experienced enough at Software applications in LEAN to say whether these are actually used in a tech company – this article is not about the applications of LEAN manufacturing methods in software development. Instead, it’s about my career. It’s even about your career.

When Do You Join a Company?#

I’m dividing this article into two parts. First, think about why you’d join a company. You’ve left an older company, and the reasons why are irrelevant – for now.

You’ve interviewed with a company, and this has involved anywhere from a couple of hours to weeks of your time. If this company has a lengthy interview process that requires a DevOps engineer to know how to invert a Binary Tree or how to write a Binary Tree where every node is a Linked List, then this process could also have taken months of your time.

You have an offer from them that cites concrete numbers that you find attractive. Let’s not kid ourselves, there’s money involved. Money is always involved.

You spoke to a couple of cool people who you may work with, or at least grab a beer with at the office parties.

You also like what the manager seems to promise that you may work on.

Think about those four points for a moment.

The first one is sunk cost. You’ve invested time into the process. You’ve invested your effort. Set this aside for now.

The second is money. Money. Money. You now have bragging rights on teamblind.com and you can leave reviews on Glassdoor.com and levels.fyi, improving the sample size for what is obviously a very positively or a very negatively skewed chart.

The third is people. You have laughed with them during the interview. Perhaps they were amazed at your data structures and algorithms prowess. Or perhaps one of them told you that your installation of Pi-Hole and Unbound could be improved; this happened to me, and I joined Merkle Science because I trust this dude. This is an interesting point, but it depends on what sort of a person you are. It might not matter to you. Your colleagues are your colleagues, and perhaps they’re not going to be your friends.

The fourth is work. Actual work. You are promised a paintbrush and the Sistine Chapel. However, it depends on your personal goals. Maybe you wanted to be a sculptor and not a painter. Perhaps you wanted to write Rust and not Golang.

So when do you join a company? Perhaps, quite simply put, when one of them is so convincing that you ignore the others. When I say one of them, I mean points two to five. If you’re joining a company because of the sunk cost fallacy, then you have different problems, and you’ll quickly move on to the next part of this post.

When Do You Leave A Company?#

When you decide to leave a company, what pushes you out the door? There are several things.

Internal politics; I know I’ve run away from that a couple of times.

Poor pay; Perhaps your manager cannot fight for your rightful worth.

Horrible work; Nothing pushes me out the door better than SharePoint and Oracle SQL.

Horrible boss; Perhaps he’s not promoting you because of some reason you think is relevant.

Horrible peers; Perhaps you think your team members are not fun to work with.

Late promotion; You didn’t get that promotion you were promised 18 months ago.

You feel like you could go on? Sure, I used to think the same thing.

But today I don’t. I think there are only three reasons why you’d want to leave. Actually there will only ever be two reasons why you’d want to leave.

Pay

People

Work

Wherever you go, whatever the company, there will only be these three things that you need to decide whether to join the company, whether to stay there, or whether to leave.

If you’re running your own company, there will only be these three reasons that you can use to hire or keep great people at your company.

But what about all the other points?

The Three Control Parameters of a Career#

This is where I come full circle with my control chart paradigm. The three points that I brought up in the previous section have everything to do with control charts. No, I don’t need you to plot statistical charts to monitor them, but you’re already plotting such charts in your head, subconsciously.

Wherever you go, whichever the company, the only three things you will feel changes in, the only three control parameters you are granted, are pay, people and work.

And this is a page I’m taking out of distributed programming, and the CAP theorem.

CAP Theorem

The CAP theorem says that for any distributed data store, you will never be able to achieve high consistency and high availability when a partition occurs.

Wherever you work, you will never, ever, achieve great pay, great people and great work.

Wherever you go, strive to get one great thing. Get great pay, great people, or great work. Just one.

Of the rest, choose a place where one of them is bearable. You will find places with great pay and okay work, or great work and okay pay, or great work and okay people, or great pay and okay people.

And the last parameter? Well… it will automatically be horrible.

It doesn’t matter how great you think your company is. One of these three features is going to be amazing.

You will love your work, you will find your colleagues okay to hang around, and you will bemoan your pay.

You will love your pay, you will find your work palatable, and you will loathe your collegues.

You will love your colleagues, you will find your pay acceptable, and you will fear signing in every day because your work is pointless.

You will love your work, you will find your pay is acceptable, and you will hate your colleagues.

You will love your pay, you will be able to withstand your colleagues, and your work will be ridiculous in your eyes.

I could go on.

The point is that irrespective of your company – irrespective of your company – this will be true. If you want to join a company, or, if you want to stay at a company, you must love one of these three things the company can give you, and you must find one of the other two to be acceptable. You will hate the third thing, so make sure it’s something you’re not passionate about.

But as a hiring manager, or a CEO or CTO, what can you do? Make pay exhorbitantly high and make the work amazing? No. That’ll only attract psychopaths who hate working together. Remember that the two things that matter to people vary from person to person. One employee might want amazing work for mediocre pay - how do you motivate her to work on database administration if what she loves is hardcore engineering? One employee might care about his colleagues, he loves to discuss the technical aspects with a team that’s the sort you hear from on stage at Goto Conf and KubeConf, and he’s okay as long as the work is bearable. Pay doesn’t matter to him. How will you try to attract this sort of employee. Then there’s the sociopath who wants amazing pay and bearable work. He’s not going to care about what sort of people he works with – he’ll be polite to them of course, but then he only cares about delivering excellent work himself. What will you offer him?

So when do you leave?

The Two Of Three Rule#

You must definitely leave when two of the three control parameters are horrible. Think of your job as a see-saw. On one side is the “great” control parameter, and on the other is the “horrible” parameter. At the center is the fulcrum, which can move either to the good side or the bad side. That’s where the third parameter is currently concentrated. And that’s the important part, surprisingly.

When this parameter is right at the center you realize that it doesn’t really make you super happy, but that it’s also not annoying you constantly. It’s a fine balance between the great parameter and the horrible parameter.

Yes, it’s not the “great” parameter, or the “horrible” parameter that decides when you will leave. Instead it’s a shift in the central parameter that you once found palpatable, bearable or just okay, when you joined.

When that parameter shifts to the horrible side, it doesn’t matter how great the other parameter is.

Your pay could be astounding, but you will not be able to work on a horrible project with horrible people.

Your colleagues could all be amazing engineers, but nothing will make you work on stuff you hate for peanuts.

Your work could be amazing and will revolutionize the world, but you cannot work on it with people you do not get along with, for horrendous pay.

If two of these parameters are on the horrible side, it doesn’t matter just how amazing the other parameter is. Your constant annoyance at the other two will upset you constantly. Indeed, the fact that a parameter you found just bearable and not an annoyance is going to annoy you multiple times more than the other horrible parameter.

At any workplace, no matter how awesome, employees will care only about one of three things. People, Pay and Work. One of these things will drive people to join you, one of them will be something they don’t really find disagreeable, and one of them will be something they would rather not talk about with their friends. If the one thing that they don’t really hate tips too far to the other end, people will leave, and improving the one thing that was the driving factor will no longer make a difference.

The Two of Three Rule

Pay, People, Work. Pick one that you need to be awesome. Pick one that you don’t mind being lack-lustre. The third one will be horrible. This rule holds at every company; indeed, it holds at any company you should and would work at. Shift the second factor, and you won’t want to work there, no matter how awesome the first factor you picked is.

The Two of Three Rule is: Pay, people, work. Two of these three things will either make you really love your job, or really hate your job.

It’s funny how this works.

When I was at Flipkart, I was paid to write about books. I am a voracious reader, or I was at one point. I was being paid to write about J.R.R. Tolkien, about Dr. Seuss, and about the Wheel of Time. Sure, there were moments I was writing about horrible books that I feel aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on, but that didn’t matter to me. So the work was okay. The pay was bad. I was earning peanuts before, and compared to that, this was okay pay, bearable pay, but it was still peanuts. The people I worked with were fun to work with. I made several friends among them, and I opened up to them like I never had with others. I was able to have lunch with them and talk about their lives. I was able to have heated discussions about comic books, about movies, and I was able to be myself.

What happened though? Why did I leave?

One day, the Catalogue team decided to scrap the books content. The team leads and the manager decided to tell me at the last minute. They didn’t even sugar coat that fact. That didn’t really matter, but it was the fact that they treated it as an afterthought that someone who constantly went on and on about how much he loved books would be “relieved” that he didn’t have to write about books again. It didn’t help that the news was also given to me by a team lead who was hired despite being clearly incompetent. I was doing the job of both team leads at that point. I had automated so much of their job, and they were really not doing much. The manager didn’t care about how much I was improving things. Instead, they chose to pull the rug from under my feet.

I left as soon as I found a new job. I wasn’t working with people I loved for horrible pay and horrible work.

Then I went to GKN. I worked on some amazing projects, and I didn’t hate the people around me. Some of them are friends today, close friends who were there for me at hard moments. Here, I got shafted with the pay once again. At one stage, my salary was revised because I managed to prove to the HR how underpaid I was – this came under the threat of leaving the company. But it was still 30% of my market value at that point.

But eventually, the people I cared about were making plans to leave, or move away. And the people who were left around me became toxic. The local leaders of my division were toxic, and that made my life hell. I couldn’t hire competent team members since I wasn’t given power to do so.

I left within 3 months. I couldn’t change their minds. I couldn’t choose the people I worked with, I couldn’t build a team to build that amazing project my German boss wanted me to build – a project I still think about fondly.

Then I joined Visa. Here I got great pay. My colleagues were good people. And the work was horrendous. I left in two years because that changed, and it would have been sooner if not for The Great Pandemic of 2020.

I’m not explaining all of this to say that my workplaces were negative. No. I still recommend Visa to all my friends who want a good place to work. Remember, the two things that matter to me out of the three might not be the same for you.

Control charts tell us that there’s something inherently wrong with a process. When a process begins to deviate from its established “norm”, it is slowly progressing to a stage where if you want it to go back to how it was, or to another acceptable state, you need to exert considerable effort. Sometimes, this won’t be in your hands. This will instead be something you need your upper management to step in and change. And, oftentimes, you’ll find that they have no horse in this race.

If you want to hire good people who will work for you for a long time and deliver great things, ask them which of the three things matter to them, and ensure that you meet those two things. The definition of a “Great Place to Work” is multi-faceted. It is very different to different people, but you will find that for a given person, these points are more or less the same unless they have a life-changing event.

When I was at Visa, I lost my left ear due to circumstances not under my control. Indeed, no one at Visa could have helped me. That changed the ball game drastically. That’s what is called a random error in a control chart. In such a scenario, no one can help you really. In such times, as a leader, the only thing you can do is try to be there for your employees. But as an employee, you need to decide what matters to you and whether staying at a place will help you achieve that sooner.

Conclusion#

So the next time you’re evaluating an offer, or if you’re evaluating whether to leave a company or to stay; or if an employee is leaving and you’re trying to figure out how to convince her to stay, remember that money isn’t always the prime bargaining chip. Sometimes money doesn’t matter. It’s the other two that upset the scale.

There are always two out of three things that make or break the experience of working at a company. To me, today, that’s money and people. Money because of the responsibilities I have, and people because I don’t just want a team, but a crew. I want a unit that functions together. The work is after the fact in my opinion. To others, those scales are definitely going to be different.

References#

These are a list of books I love recommending if you’re interested in the topic of statistics and process control.

Edward Deming - Out of the Crisis

Walter A. Shewart - Statistical Method From the Viewpoint of Quality Control

Taiichi Ohno - Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production

Taiichi Ohno - Workplace Management

These books were written in a time where statistical quality control was applied predominantly to manufacturing processes, but I’d recommend looking at them through the lens of a general engineer, as opposed to a software engineer. If you ever find yourself wanting to discuss these topics, I’m always available. Reach out to me on Twitter.