Dear Mr. Debroy#

Note

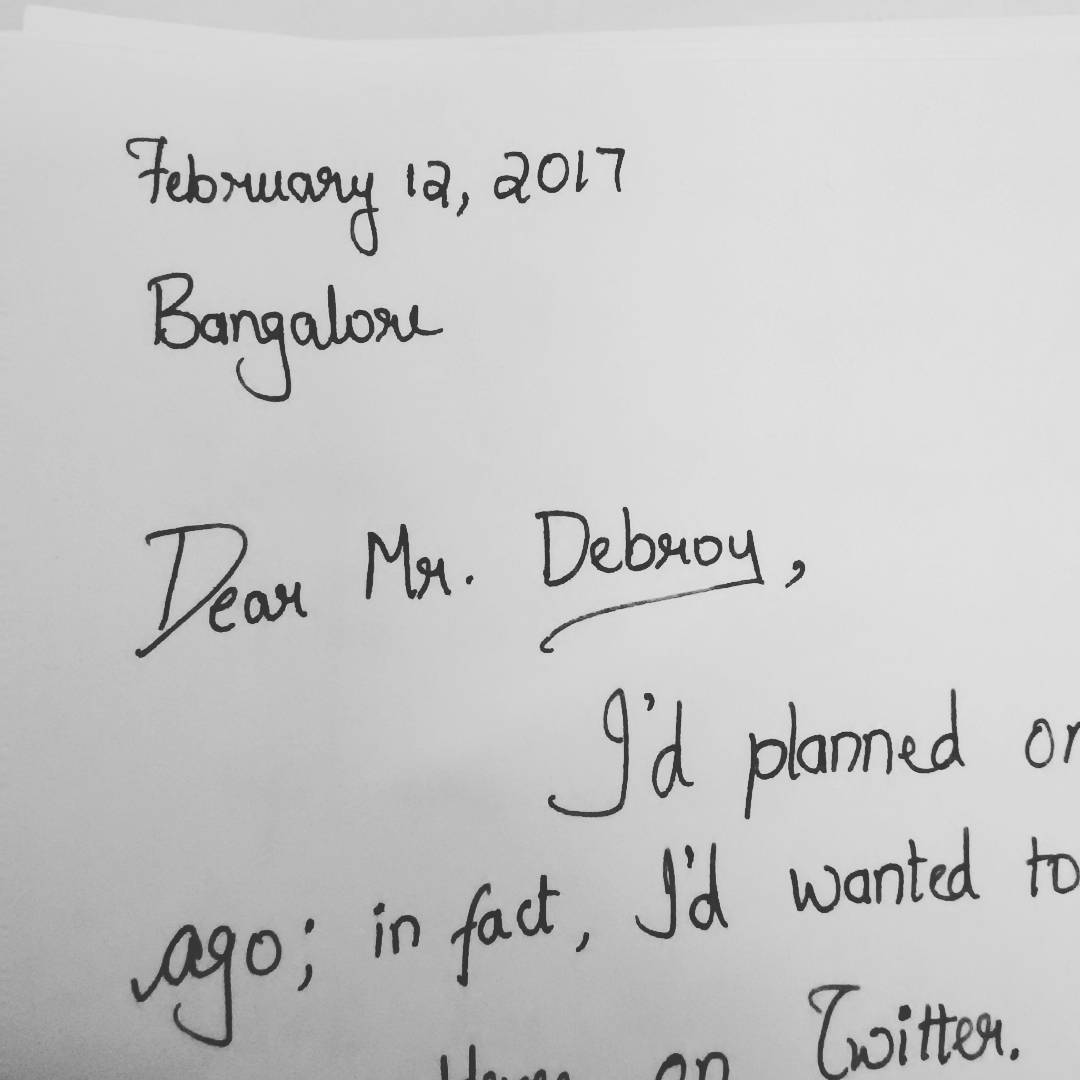

The following is the content of handwritten letter I sent to Mr. Debroy dated Feb 12th, 2017. I’ve reproduced it in its entirety here.

Dear Mr. Debroy,

I’d planned on writing this letter a few weeks ago. I drafted it a month ago but I wanted to rewrite it entirely because I wasn’t entirely happy with the first draft. I do not know when this will reach you, but I believe in our postal service. Thank you for giving me your address by the way.

My name is Vinay Keerthi, and I am writing to you regarding your translation of the Mahabharata.

I come from an orthodox South Indian Brahmin family. I had the fortune of being introduced to our country’s itihasa by a rather liberal paternal grandfather. He imbued me with a fascination for stories of all kinds. Primarily though, I remember his retelling of the Ramayana, the Vishnu Purana, and the Shiva Purana. I vividly remember his rendition of the War in Lanka.

He passed in 1996, when I was 8, and that severed my classical education. But his stories remained with me, and I was still hungry for more.

I began reading at an early age. I’d read a children’s version of the Ramayana, a collection of stories from the Jatakas, the Hitopadesa and the Panchatantra. I also read a few stories from the Amar Chitra Katha series.

I knew more stories than most kids my age, but what my childhood appeared to lack was the experience of the Mahabharata. I had a very vague idea of it, but mostly that it involved Krishna.

I remember my grandfather resting in a comfortable chair to watch the old TV series on DD2. I remember a scene or two. I also remember it being covered in school. I remember yawning during Hindi class. That reinforces my faith that the fastest way to ensure kids don’t learn our classics is to shove them down their throats in high school. I’m sorry but far too few teachers are good with teaching.

I loved stories and I grew up without access to the Mahabharata.

Late in high school, I encountered the Rajagopalachari version, and frankly, I did not enjoy it as much as I did his Ramayana. But it piqued my interest.

In the summer of 2002, I inherited my maternal grandfather’s vast collection of the Bhawan’s Journals: a few hundred of from from the 40s and 50s. In reading these, I discovered Kulapathi K. M. Munshi. And, by extension, I discovered his Krishnavatara series. I fell in love with Munshiji’s writing. How fortunate the Bhawan was to have him at the helm!

Munshi’s books did what the rest could not. They made me want to read the Mahabharata in its true form: or as close to an unabridged translation as I possibly could.

Between 2010 and 2011, I was working at the Indian Institute of Science. On my way back home, I often visited a bookshop where I knew the owner quite well. As I was about to ask him if there was a “good version” of the Mahabharata, he stopped me.

“If you want the full story, read this.”

He said, handing me a copy of an oddly bound book with curious symbols on the cover. It said:

The Mahabharata 1: *Translated* by Bibek Debroy

Translated. Not a retelling. Not an abridgement. I was sold.

The shopkeeper only had 3 volumes back then. So I decided to wait util I could buy the complete set. I wanted to read this at a stretch. So, I waited.

In 2015, I learnt that you’d finished the series. I leapt at the chance and bought a box set. I love the new black covers.

I devoured the first book in a week, on my daily commute. As I read the book, in the minute details that crept in, I was flooded by memories. My paternal grandfather had told me stories from the Adi Parva. He’d told me of Shakuntala and Dushyanta, of Parashurama, of Takshaka and Astika, of Jaratkaru and his condition that his wife must have the same name, and of Ganga’s descent to our world at the behest of Bhagiratha. My grandfather had told me stories and so many more. I just did not know that these were from the Mahabharata.

When I realized this, I stopped reading. I realized that I was making a mistake.

I decided to wait.

This was the Mahabharata. I could not read this in a concrete jungle. I wanted to read it without distractions. I wanted to read it where no one would disturb me.

So, I did.

I wanted to read your translation of the tale that contains all tales in a place that was as hallowed as the stories themselves.

So, I did.

In December 2016, I took a month off from work and went to the land of my birth. I went to Kishkinda. I went to Hampi.

For 18 days, I sat in the ruins of Vijayanagara, near the river Tungabhadra, and read the Mahabharata.

I wanted to read these stories in Hampi, a place where bards probably recited versions of it to the King, centuries ago, to earn their keep.

I wanted to read the Mahabharata in plain sight of a river.

So, I did.

On the first day, I sat in an abandoned temple to Vishnu and reread the first book. As I read stories of the Adi Parva, I was enveloped by the breeze of the hilltops of Hampi. Langoors frolicked in the trees and tried to steal fruits visitors offered to the temple below the hill where I read. That temple, the locals claim, is where Rama meets Sugreeva. As I read, a lone flautist played from across the Tungabhadra, and his song blended with the cries of the cheeky monkeys and the whispers of the flowing river.

There, over the next three days, I read of Ganga and Shantanu, Satyavathi and Parashara, and learnt of the birth of Krishna Dvaipayana Vyaasa.

As I progressed, I left that temple and sought the shade of a lone tree from where I could see several prominent hills in Kishkinda. As I read the next two books there, I must have been a strange sight to the tourists. SOme commented that I looked like a rishi!

As I read the Mahabharata, I began to question it continuously. Shantanu’s love for Satyavathi, the terrible oath that Gangeya took for his father’s sake, and, by extension, Puru’s sacrifice for the sake of Yayati, made me wonder if any son today could do that for his father.

Bhishma of the Terrible Oath indeed!

After I read of the births of the Pandavas and the Kauravas, I climbed a hill where the rishi Matanga is supposed to have cursed the Vanara King Vali, and read of the misfortunes of the Pandavas.

I read how Bhima bullied the Kauravas as a child. What else could an elder brother like Suyodhana do but grow to despise him? It is so easy to paint the Kauravas as villains but Dharma is way to subtle for that.

I sat in an abandoned temple to Shiva, long desecrated by Muslims, as I read of Shakuni’s machinations. The temple is adored with symbols of a boar, and for that reason, is called the Varaha temple. Here, I read of the dice game at the sabha built by Maya.

Why?

If sons back then respected their fathers enough to give up their youth and sexual pleasure, why did Duryodhana not heed his father’s words?

Dharma? Did Dharma compel the Son of Yama to wager Panchali away?

Time and again Shakuni resorts to deceit and tells Yudishtira:

“I have won!”

What Dharma is this that allows it?

Such irony that in a Sabha built by Maya, Dharma had to fall before Shakuni’s illusions.

I climbed 500 odd stairs to a temple of Hanuman, atop a hill called Anjanadri - which locals claim as his birthplace. There, under yet another lonely tree, I pondered about the foolishness of the Sons of Dhritarashtra.

Surely, they knew it was coming.

Vyaasa’s story makes it seem like Parashurama’s slaying of Kartavirya Arjuna and his clansmen was a kind of preparation for the war that was about to follow on that very soil.

Kurukshetra.

War.

But there already was war, right?

I enjoyed the Virata Parva the most. Narada’s account of Nala and Damayanti was very new to me. I’d never heard of them before. Narada offering to bestow Dharmaraja with the knowledge of dice games - the knowledge Nala was known - seemed just. If only Yudishtira knew dice before his match with Shakuni.

How subtle is Dharma?

The day I finished the Virata Parva, it rained in Hampi. In December! The cyclone from the Bay of Bengal caught up with me. Or, like my aunts claim, King Virata’s love for the rain knows no bounds. I should read that portion once a month to save Bangalore from its water woes then.

I laughed at the end of that Parva. How effortlessly Arjuna dismisses the sons of Dhritarashtra. In a poetic way, this should have been the end.

Suyodhana should have listened.

Naturally, he would not.

All my life I have wanted to be a writer. With my love for stories, I began making up stories of my own as a child. I love the Mahabharata for its structure, for its flow, and for its unfathomable scale. The Mahabharata is impossible to avoid, I believe. Almost every Indian will at least assume that it is about the war.

I wonder what it would feel like to read the Mahabharata knowing nothing about it. What an experience that would be! No wonder Lomaharshana could make people get goosebumps!

One constant figure in the Mahabharata that I feel only pain for is Karna. My maternal aunt tells me that he is her favorite character. I can understand why.

There is a beautiful Telugu movie called Daana Veera Soora Karna. Self-explanatory, don’t you think?

Karna.

Oh, Karna!

Why? Why did he have to be so giving? Why couldn’t he say no? There is such a thing as being too generous. Even after his father beseeched him to refuse Indra’s plea, he gave up his kavacha kundalam.

Is this Dharma?

I sat at the entrance of a temple to Vishnu that has not seen worship in over four-hundred years and asked the idol if he thought it was fair.

Naturally, he was silent.

Flow.

As a writer, it is hard to ignore the flow of the Mahabharata. As soon as he receives omniscience, Sanjaya cries out that all is lost. Bhishma has fallen.

How cruel is it, then, for the story to recap events from the first day?

But how wondrous it is to know that the reader is not alone in his or her doubts. Gandhivadhanva, Partha Arjuna has his doubts as well.

Yet, he is fortunate to have the wielder of the Sudharshana as his charioteer.

The Bhagavad Gita is such an icon part of the Mahabharata. I smiled as I read your translation.

So many footnotes! Completely necessary of course. But I could tell that the Gita itself needed much more explanation.

Bhishma.

Gangeya is the first character in this story I completely respect. What is Dharma if not Bhishma? Why couldn’t he have been King? Such a loss!

As Bhishma stood, the battle followed all the rules of conflict.

So, after his fall, chaos erupted.

That image, of the aged warrior who hunbled Bhargava Rama of the Battle Axe, lying on a bed of arrows, is haunting.

As Drona takes control, Dharma seems to whither.

Angered by Duryodhana’s doubt in his abilities, Drona orders his army to form the Chakravyuham formation.

Abhimanyu.

The way that young boy was slain was far too cruel. I felt so angry at Jayadratha.

Where was Dharma then? Does it not protect those who protect it?

Why did Dharmaraja have to ask such a young boy to break in?

Dharma. All of the Mahabharata is about Dharma, or one’s interpretation of it. Was Abhimanyu wronged? Or was Arjuna committing sin as he shot Bhurishrava in the arm to save Yuyudhana? As Jayadratha falls, Karna vows to use the Pashupati against Arjuna and Drona struggles to prove his worth. Dharma!

Again, where is Dharma in the killing of Drona by tricking him into believing his son has fallen?

Is Ashwattama’s anger not justified?

As I read of Karna’s death, the sun was setting. The orange star was just behind the main gopuram of the Virupaksha temple. I looked at it from three kilometres away, by an abandoned temple to Narasimha.

Karna. Oh, Vaikartana! how can anyone not cheer for your? When faced with the task of killing Ghatotkacha, you used the very weapon you’d saved to use on your nemesis Partha. Who could be more deserving of cheer?

Even now I feel so much anguish at his death.

For the death of Suyodhana, I sat near the Stone Chariot. It seemed fitting that I sit in the Vijaya Vittala Temple for this portion.

It was very crowded but I was lost in this tale.

I loved the portion where Samkarshana Balarama calls Suyodhana out to face the Pandavas. How much Duryodhana must have loved his teacher to leave the depths of lake Dvaipayana!

Again, we witness Krishna’s guile.

Suyodhana could have chosen to fight any one of the Pandavas. but Krishna knew.

He knew who he would pick.

An equal.

Bhimasena.

How? Why do I feel the most sympathy for Suyodhana? I did not expect this.

In his death, I grieved as though my kin had passed.

Where was Dharma?

And what of Dhritarashtra and Gandhari? What of Kunti who had just lost her first son? And what of Subhadra? And Droupadi? Her honour had been restored at what cost? And what of Uttara? How could anyone stay sane after watching the wife of Karna lament for him?

What does Dharma mean when all those who fought for it lay dead?

Why! Why couldn’t Suyodhana share? Wasn’t all of this that Yadava’s fault? I agree with Gandhari.

I can only imagine how much Dhritarashtra wanted to crush Bhima. Who can blame him?

All that followed was destruction.

Destruction of the Yadavas. The death of Krishna.

Is this victory?

Or is this the way of Dharma?

Fitting, then, that even in death, Dharmaraja needed testing. What manner of soul could pass through this without scars?

Truly fitting.

Mr. Debroy, I could go on and on for ten more pages and still not run out of things I would like to share with you.

I have read the Bible, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Homeric Epics, a few tales from the Norse Eddas, and Buddhist stories, and nothing comes close.

Everything pales in comparison. This story has it all. I can only hope it reaches more people.

Three years ago, under the weight of several rejection letters, I put my writing aside to focus on my career instead. But reading the Mahabharata by the Tungabhadra has given me what I needed.

Peace.

This is what anyone should hope for, isn’t it?

Peace.

It’s more than what the Pandavas got for all their troubles.

I have so many questions sir. In the entire story, I couldn’t help notice that Ganesha was never even mentioned.

I was partly named after him, so naturally I searched for his name. It is so odd.

I have other questions, on the historicity of this tale, but, I digress.

Mr. Debroy, thank you.

I cna only imagine how you did it. Managing your career, your family, and translating the greatest story of them all.

I have only one thing to say to anyone who asks me about the Mahabharata.

Bibek Debroy’s translation is the only one you should read. Unless you can read Sanskrit.

Thank you sir.

Thank you for giving us this. I will return to Hampi to read the Harivamsha and the Ramayana.

I hope this letter reaches you in good health.

Give my regards to your family. I have them to thank as well.

Once again, sir, thank you for bringing a few memories of my grandfather back to me.

Regards,

Vinay Keerthi